This article is about the most common aging brain problem that you may have never heard of.

While leading a fall prevention workshop a few years ago, I mentioned that an older person’s walking and balance problems might well be related to the presence of “small vessel ischemic changes” in the brain, which are very common in aging adults. (This is also called “white matter disease.”)

This led to an immediate flurry of follow-up questions. What exactly are these changes, people wanted to know. Do they happen to every older adult? Is this the same as vascular dementia? And how they can best help their parents with cognitive decline?

Well, these types of brain lesions don’t happen to every older person, but they do happen to the vast majority of them. In fact, one study of older adults aged 60-90 found that 95% of them showed signs of these changes on brain MRI.

In other words, if your older parent ever gets an MRI of the head, he or she will probably show some signs of these changes.

So this is a condition that older adults and families should know about. Furthermore, these changes have been associated with problems of consequence to older adults, including:

- Cognitive decline,

- Problems with walking or balance,

- Strokes,

- Vascular dementia.

Now, perhaps the best technical term for what I’m referring to is “cerebral small vessel disease.” But many other synonyms are used by the medical community — especially in radiology reports. They include:

- White matter disease

- Small vessel ischemic disease

- Brain lesions

- Periventricular white matter changes

- Perivascular chronic ischemic white matter disease of aging

- Chronic microvascular changes, chronic microvascular ischemic changes

- Chronic microvascular ischemia

- White matter hyperintensities

- Age-related white matter changes

- Leukoaraiosis

In this post, I will explain what all older adults and their families should know about this extremely common condition related to the brain health of older adults.

In particular, I’ll address the following frequently asked questions:

- What is cerebral small vessel disease (SVD)?

- What are the symptoms of cerebral SVD?

- How is cerebral small vessel disease related to vascular dementia and cerebrovascular accidents?

- What causes cerebral SVD?

- How can cerebral SVD be treated or prevented?

- Should you request an MRI if you’re concerned about cerebral SVD?

I will also address what you can do, if you are concerned about cerebral SVD for yourself or an older loved one.

What is cerebral small vessel disease?

Cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is an umbrella term covering a variety of abnormalities related to small blood vessels in the brain. Because most brain tissue appears white on MRIs, these abnormalities were historically referred to as “white matter changes” or “white matter disease.”

Per this medical review article, specific examples of cerebral SVD include “lacunar infarcts” (which are a type of small stroke), “white matter hyperintensities” (which are a radiological finding), and “cerebral microbleeds” (which means bleeding in the brain from a very small blood vessel).

In many cases, cerebral SVD seems to be a consequence of atherosclerosis affecting the smaller blood vessels that nourish brain tissue. Just as one’s larger blood vessels in the heart or elsewhere can accumulate plaque, inflammation, and chronic damage over the years, so can the smaller blood vessels.

Such chronic damage can lead the small blood vessels in the brain to become blocked (which starves brain cells of oxygen, and which we technically call ischemia), or to leak (which causes bleeding, which we call hemorrhage and can damage nearby brain cells).

When little bits of brain get damaged in these ways, they can change appearance on radiological scans. So when an MRI report says “white matter disease,” this means the radiologist is seeing signs that probably indicate cerebral SVD.

(Note: In this podcast episode, a UCSF brain health expert explains that although cerebral small vessel disease is probably the most common cause of white matter changes in older adults, it’s not the only condition that can cause such changes. )

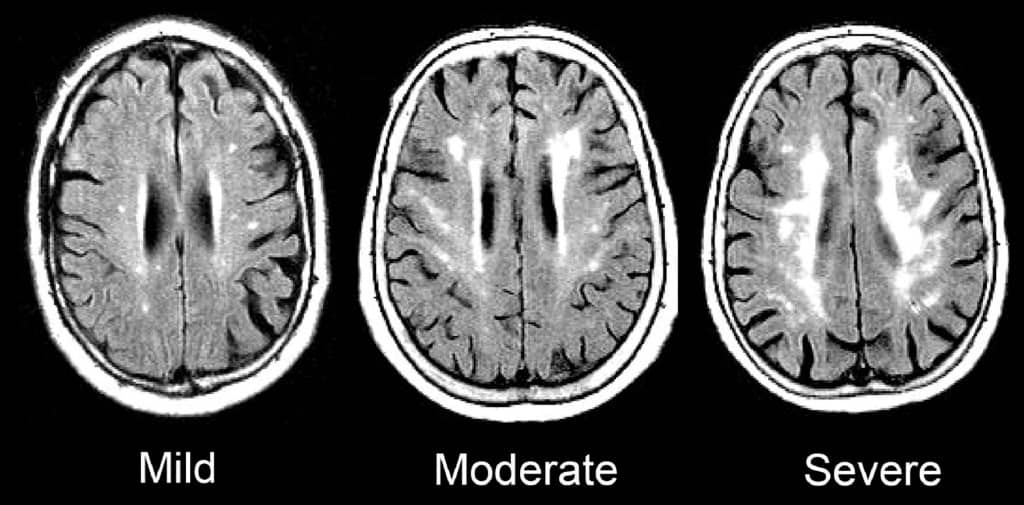

Such signs of SVD may be described as “mild”, “moderate,” or “severe/extensive,” depending on how widespread they are.

Here is an enlargement of a good image, from the BMJ article “Changes in white matter as determinant of global functional decline in older independent outpatients.”

What are the symptoms of cerebral small vessel disease?

The severity of symptoms tends to correspond to whether radiological imaging shows the white matter changes to be mild, moderate, or severe.

Many older adults with cerebral SVD will have no noticeable symptoms. This is sometimes called “silent” SVD.

But many problems have been associated with cerebral SVD, especially when it is moderate or severe. These include:

- Cognitive impairment. Several studies, such as this one, have found that cerebral SVD is correlated with worse scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam. When problems with thinking skills are associated with SVD, this can be called “vascular cognitive impairment.”

- Problems with walking and balance. White matter lesions have been repeatedly associated with gait disturbances and mobility difficulties. A 2013 study found that moderate or severe cerebral SVD was associated with a decline in gait and balance function.

- Strokes. A 2010 meta-analysis concluded that white matter hyperintensities are associated with a more than two-fold increase in the risk of stroke.

- Depression. White matter changes have been associated with a higher risk of depression in older people, and may represent a contributor to depression that is particular to having first-time depression in later life.

- Vascular dementia. Signs of cerebral SVD are associated with both having vascular dementia, and eventually developing vascular dementia.

- Other dementias. Research suggests that cerebral SVD is also associated with an increased risk — or increased severity — of other forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Autopsy studies have confirmed that many older adults with dementia show signs of both Alzheimer’s pathology and cerebral small vessel disease.

- Transition to disability or death. In a 2009 study of 639 non-disabled older persons (mean age 74), over a three-year follow-up period, 29.5% of participants with severe white matter changes and 15.1% of participants with moderate white matter changes developed disabilities or died. In comparison, only 10.5% of participants with mild white matter changes transitioned to disability or death over three years. The researchers concluded that severity of cerebral SVD is an important risk factor for overall decline in older adults.

So what does this all mean, in terms of symptoms and cerebral SVD? Here’s how I would boil it down:

1.Overall, older adults with any of the problems listed above have a high probability of having cerebral SVD.

2. But, many older adults with cerebral SVD on MRI are asymptomatic, and do not notice any difficulties. This is especially true of aging adults with mild cerebral SVD.

3. Older adults with cerebral SVD are at increased risk of developing the problems above, often within a few years time. This is especially true of people with moderate or severe cerebral SVD.

How is cerebral small vessel disease related to vascular dementia and cerebrovascular accidents?

The term “vascular dementia” means having dementia that is mostly due to having had problems with the blood vessels in the brain.

(For more on the definition of dementia and vascular dementia, see here: Beyond Alzheimer’s: Common Types of Dementia in Aging.)

The brain has some large blood vessels; when a person develops a clot or bleed related to a large blood vessel, this causes a major stroke, also known as a cerebrovascular accident.

It is possible to get dementia after a major stroke. However, in older adults, it’s probably more common to develop vascular dementia due to injuries to the small vessels of the brain. But again, as I explained above: not everyone with signs of cerebral small vessel disease ends up developing cognitive impairment or dementia.

What causes cerebral small vessel disease?

This is a topic of intense research, and the experts in this area tend to really nerd out when discussing it. (Read the scholarly papers listed below to see what I mean.) One reason it’s difficult to give an exact answer is that cerebral SVD is a broad umbrella term that encompasses many different types of problems with the brain’s small blood vessels.

Still, certain risk factors for developing cerebral SVD have been identified. Many overlap with risk factors for stroke. They include:

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia (e.g. high cholesterol)

- Atrial fibrillation

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Age

- Inflammation

There is also evidence that Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral small vessel disease frequently co-exist in older adults, and might interact to accelerate cognitive decline.

How can cerebral small vessel disease be treated or prevented?

Experts are still trying to figure out the answers to this question, and research into the prevention of cerebral SVD is ongoing.

Since worsening of white matter disease is often associated with clinical problems, experts are also trying to determine how we might prevent, or delay, the progression of SVD in older adults.

Generally, experts recommend that clinicians consider treating any underlying risk factors. In most cases, this means detecting and treating any traditional risk factors for stroke.

(For more on identifying and addressing stroke risk factors, see How to Address Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Better Brain Health: 12 Risks to Know & 5 Things to Do.)

To date, studies of hypertension treatment to prevent the progression of white matter changes have shown mixed results. It appears that treating high blood pressure can slow the progression of brain changes in some people. But such treatment may be less effective in people who are older than 80, or who already have severe cerebral SVD.

In other words, your best bet for preventing or slowing down cerebral SVD may be to properly treat high blood pressure and other risk factors before you are 80, or otherwise have significant SVD.

Furthermore, experts don’t yet agree on how low to go, when it comes to optimal blood pressure for an older person with cerebral small vessel disease. (This article explains why this has been difficult to determine.)

For now, to prevent the occurrence or progression of cerebral small vessel disease, it’s reasonable to start by observing the hypertension guidelines considered reasonable for most older adults: treat to a target of systolic blood pressure less than 150mm/Hg.

Whether to treat high blood pressure — and other cardiovascular risk factors — more aggressively should depend on an older person’s particular health circumstances. I explain a step-by-step process you can use (with links to related research) here: 6 Steps to Better High Blood Pressure Treatment for Older Adults.

You can also learn more about the research on CSVD and the effect of treating blood pressure here: The relation between antihypertensive treatment and progression of cerebral small vessel disease.

Not necessarily. In my opinion, older adults should only get MRIs of the brain if the following two things are true:

- They are experiencing worrisome clinical symptoms, and

- The results of the MRI are needed to decide on how to treat the person.

For most older adults, an MRI showing signs of cerebral SVD will not, in of itself, change the management of medical problems.

If you have high blood pressure, you should consider treatment. If you are having difficulties with walking or balance, signs of cerebral SVD do not rule out the possibility of other common causes of walking problems, such as medication side-effects, foot pain, neuropathy, and so forth.

What if you’re concerned about memory or thinking problems? Well, you probably will find signs of cerebral SVD on an MRI, just because this is a common finding in all older adults, and it’s especially common in people who are experiencing cognitive changes.

However, the MRI cannot tell you whether the cognitive changes you are noticing are only due to cerebral SVD, versus due to developing Alzheimer’s disease, versus due one of the many other dementia mimics. You will still need to pursue a careful evaluation for cognitive impairment. And no matter what the MRI shows, you will likely need to consider optimizing cardiovascular risk factors.

So in most cases, a brain MRI just to check for cerebral SVD is probably not a good idea.

However, if an MRI is indicated for other reasons, you may find out that an older person has mild, moderate, or severe signs of cerebral SVD. In this case, especially if the cerebral SVD is moderate or severe, you’ll want to consider taking steps to reduce stroke risk, and also to monitor for cognitive changes and increased disability.

What to do if you’re worried about cerebral small vessel disease

If you are worried about cerebral SVD, for yourself or for an older relative, here a few things you can do:

- Talk to your doctor about your concerns. You may want to discuss your options for optimizing vascular risk factors, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, high blood sugar, smoking, and others. For more on identifying and addressing stroke risk factors, see How to Address Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Better Brain Health: 12 Risks to Know & 5 Things to Do.

- Remember that exercise, a healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean diet), good sleep, stress reduction, and many other non-pharmacological approaches can help manage vascular risk factors. Lifestyle approaches are safe and usually benefit your health in lots of ways. Medications to treat high blood pressure and cholesterol should be used judiciously.

- If an MRI of the brain is clinically indicated — or if one has recently been done — ask the doctor to help you understand how the findings may correspond to any worrisome symptoms you’ve noticed. But if you’ve been worried about cognitive impairment or falls, remember that such problems are usually multi-factorial (i.e. they have multiple causes). So it’s best to make sure the doctors have checked for all other common contributors to thinking problems and/or falls.

If you want to learn still more about cerebral small vessel disease, here are some scholarly articles on the subject:

- CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review (2019)

- Mechanisms underlying sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging

- Causes and consequences of cerebral small vessel disease. The RUN DMC study

- Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (2011)

- Early Cerebral Small Vessel Disease and Brain Volume, Cognition, and Gait

- Cardiovascular risk factors and small vessel disease of the brain: Blood pressure, white matter lesions, and functional decline in older persons

I also recommend listening to this very informative podcast interview, with Dr. Fanny Elahi of the UCSF Memory and Aging Center: 084 – Interview: Understanding White Matter Changes in the Aging Brain.

Note: We’ve hit 300+ comments on this article! So we’re closing comments for this article. Thank you for your interest!

Note: This article has generated a lot of questions from people under age 60. If that describes you, please read below:

- Please read the article on “Early Cerebral Small Vessel Disease,” the full article is available for free. This describes SVD found in people aged 40-75. In this study, 2-3% of participants in their 40s showed signs of cerebral SVD.

- You can check for more recent research on this topic by entering the above article at scholar.google.com, and then click the “Cited by” link to find newer articles that reference this article.

- I do not know much about cerebral SVD in younger adults; this is not the population that I personally treat nor read much about. (I’m already quite busy trying to keep up with research related to older adults.)

- As best I can tell, most of what we currently know about health outcomes related to cerebral SVD is based on the studies of older adults. It is not clear to me whether people with cerebral SVD at younger ages should expect similar outcomes. I will not be able to answer most questions related to cerebral SVD in people under age 60.

- If you are concerned about what caused your MRI findings, or what they might mean for the future, please don’t ask me to tell you, because I don’t have these kinds of answers and I cannot quickly find them online.

- You should start by talking to your usual doctors, and perhaps a neurologist.

- If you would like to learn more, consider finding someone specialized in white matter disease in younger adults (e.g. someone doing and publishing research on this topic). Such experts are usually based at an academic medical center. Good luck!

Susan says

Interesting read. I have been doing a lot of my own research because I am one who wants to know answers, even if there is no cure. I am trying to figure out my Mom’s issue. She is 94 years old. Her last MRI was in 08/2016. At that time, she was having issues finding the right words (and was frustrated). The MRI impression indicates she has “Advanced chronic small vessel ischemic disease”, along with “mild atrophy” and “Remote infarct within left basal ganglia.” There was “No acute intracranial process.”

She has always been active, so it is hard to see her decline so quickly. Since 2016, her aphasia has progressed to where most of what she says is hard to understand. Though she has not had another MRI, I am told that the aphasia is from more strokes/TIAs that have gone undetected. (Her last known stroke was in 2012.) She has been on Plavix since 2013 after a heart attack.

She does have gait issues and does lose her balance (and falls) quite often. That sounds like SVD is the cause. She has not been diagnosed with dementia. She does get confused at times, though. She appears to know what it going on. But, with her aphasia, it is hard to say if she is just saying the wrong things… Would SVD lead to aphasia? I would like to know what we can expect with her continued decline. We have in-home hospice care. Mom is still mobile, but needs personal care assistance. Hospice lists her terminal illness as aphasia. Seems odd to me….

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Sorry to hear of your mother’s decline. At age 94, it’s probably due to lots of problems progressing and accumulating. Small strokes and other forms of vascular damage to the brain could certainly cause or worsen aphasia. In fact, this patient education handout on basal ganglia stroke lists aphasia as a potential effect: static/file/caregiving_ten_tips.authcheckdam.pdf

Problems with balance and falls are almost always multifactorial in people her age. Most likely SVD is a factor but she also probably has other issues that are common causes or contributors, such as low leg strength. I have more here: Why Older People Fall & How to Reduce Fall Risk

Honestly, you can try to research the whys, but ultimately it tends to be most productive to focus on identifying issues that can perhaps be corrected or better managed, such as medication side-effects.

The other thing that is often important at this stage is to think of quality of life and do what you can to help her enjoy whatever time she has left. Of course, walking better might improve her quality of life, but is it worth pushing her to do physical therapy or some strengthening exercises at this point? There is no exact right answer, generally what is best is for patients and families to get their doctors to help them weigh the likely benefits and burdens of your available options.

If she is on hospice, they should be able to tell you more about what her recent decline might mean, and what to expect. Try to treasure the time you have with her now. It is normal to worry, and also to feel grief. You’re seeing your previously active mom decline quickly, it must be very hard. Be sure to find some support for yourself.

Some people her age do stabilize on hospice, others don’t. Finding a way to come to terms with the uncertainty is one of the hardest things about this time. Good luck and take care.

Cathy says

I so appreciate all the information you are providing! My partner is a 64 year old female. She was a very well respeced national educator. Mentally quick and very social. For the last 4 yeasrs she has been having problems with visual spatial, language and executive function. She is depressed and no longer able to work or drive because of this. I am her care taker. Her recent MRI says she has moderate generalized volume loss and White Matter disease – probably on basis of small vessel disease that has progressed since last MRI 3 years ago. There is a 1.2 cm extra-axial, dural based mass along the squamous temporal bone on the right. As a child she had many xray treatments on her birth mark located on right temple and eye. Trying to figure out what is causing her cognitive problems. Her Thyroid, blood sugar, blood pressure and Cholesterol are all in normal range. None smoker. Used to be very active and work out every day. Now take only short walks. Rather stay home. Mother had early onset Alzheimers.

Wondering if the small vessel disease and the mass on the temporal bone could be the cause. We have had no help from primary doctor. The Alzheimer doctor she saw 3 years ago said not MCI. The stress of trying to find out what is causing all this has become very stressful for me. Any thoughts would be appreciated.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Sorry to hear that your partner is having all these difficulties, they do sound very worrisome.

Especially given her family history of early Alzheimer’s, I would recommend she get re-evaluated. I don’t generally recommend a specialized memory center for people who are in the 80s or older, but I do think it’s a good idea for people who are younger, as she is. It sounds like she saw a specialist three years ago but in three years a lot of things can change, and it sounds like her symptoms are much more significant.

I am not a neurologist so not very well positioned to say what impact her tumor might have. It does sound small to be causing all the symptoms you describe.

I have information on how we evaluate dementias such as Alzheimer’s here:

How We Diagnose Dementia: The Practical Basics to Know

Good luck, I hope you get some answers soon.

Andrea A Russell, Ph.D. says

Thank you for this excellent information. I do need to think more like a geriatrician both for myself and my aging patients. Keep writing, please!

Shae says

I have read all the comments here and have noticed a large number of women with this issue who are also in the peri-menopausal to newly menopausal age range. Hormones are a vastly understudied and misunderstood factor in so many things in our lives. My health was tipped upside down as my hormones diminished, and I have gotten some of my well-being back by restoring my levels. What is your opinion on them regarding brain health and CSVD?

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

I don’t personally work with women who are peri-menopausal (too young for me!), but yes, there is ample evidence that sex hormones have a significant effect on neurons (brain cells), how those neurons function, and also on cardiovascular health.

I took a quick look in the literature and there does yet seem to be much known about how sex hormones affect the health and function of small blood vessels in the brain, but research is ongoing. Here are few articles that may be of interest:

Estrogen Effects on Cognitive and Synaptic Health Over the Lifecourse

Duration of Reproductive Life Span, Age at Menarche, and Age at Menopause Are Associated With Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Women

Understanding the broad influence of sex hormones and sex differences in the brain

My impression is that it is too soon to know just how one’s sex hormones might be corrected/adjusted, to minimize the risk of cerebral small vessel disease in particular. But presumably whatever seems most effective at minimizing cardiovascular risk factors should help.

Shae says

“My impression is that it is too soon to know just how one’s sex hormones might be corrected/adjusted, to minimize the risk of cerebral small vessel disease in particular.”

Your statement is both true and tragic. There are billions of women on this planet, and more and more of us are making it to menopause and beyond, yet so little is known about cardiovascular diseases and their relationships to our hormones. Heart disease and related conditions affect such a profound proportion of us, killing five times as many of us as breast cancer, and yet we are only now beginning to ask the important questions and do the research.

The WHI study that came out in 2002 painted all hormone replacement as bad, and as a result, doctors around the world pulled woman off HRT in droves. Yet now we know that the study was deeply flawed. People should have asked long ago why it was that the female hormones that protected us so well from cardiovascular disease early on, suddenly turned on us in later years. That defied logic on every level.

Anyway, women across the board are understudied, under diagnosed, and under treated when it comes to heart disease. In the past, researchers did not want to study us because our hormones complicated things and added too many parameters. But it is time now for everyone to get with the program. I was diagnosed with CSVD just last week, and I would really like to know what hormones can do to possibly slow this progression. The clock is ticking.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Agree, women have historically been inadequately studied in medicine and we are far behind where we should be. Let’s hope we see some serious progress in the next few years.

Susan Stewart says

This information is a follow-up from my message on 1-25-18 and your response on 1-26-18. I really appreciate the help you provide. It is invaluable to so many who are desperately going through a difficult time. I will be going to an appointment (Psychiatry) with my 82 year old husband in 2 days. After completing the MOCA I think the recommendation will be SSRIs for anxiety and AChE inhibitors. He has taken Zoloft, Xanax, Trazodone previously with side effects of disorientation, increased confusion. I didn’t see in the material on your site that you mentioned AChEs and would like your opinion. What do you think of the C-Reactive protein tests? I noticed the material indicated that if the impairment is not due to neurodegeneration it often remains stable and can improve. I realize this would be expecting too much with CVD. Is there a possibility that the carotid artery blockage could cause restriction of the blood flow to the brain resulting in ischemia? If so, it would not be resolved and continue to cause critical problems. I question whether to see a Neurologist concerning this problem. It is very possible that he had a TIA with no residual that showed up on the MRI. His Carotid test shows moderate blockage. He had leg weakness at the time. Thank you for what you do. Susan Stewart

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

I cover acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in this article: 4 Medications to Treat Alzheimer’s & Other Dementias: How They Work & FAQs.

I address C-reactive protein in my recently published article on cardiovascular risk factors.

As I said before, it sounds like he’s been getting good medical management to address his cardiovascular risk factors. If his BP is under control and he is taking the statin and antiplatelet agent, I think it’s unlikely that he’ll benefit from further evaluation or intervention of CRP or carotids.

You should ask his doctors, but probably he’s more likely to benefit from more holistic approaches that will help his brain and body. I would definitely recommend regular exercise and getting outside regularly, and I cover some other important lifestyle approaches in the article on cardiovascular risk factors.

SSRI-type antidepressants may help some people with cognitive symptoms, although the research is mixed. Usually it’s worth a try to see if it helps, but again, the best is to take a multi-pronged approach to depressive symptoms and again, encourage exercise, activities, and so forth. If he didn’t tolerate sertraline (Zoloft), the other SSRI we often use for people like him is citalopram (Celexa). The others tend to have more interactions or problematic side-effects, especially paroxetine (Paxil), which is anticholinergic.

I don’t mean to sound discouraging, but most people his age, with the issues you describe, do continue to decline cognitively. The right kind of oversight (lifestyle factors plus avoiding medications that dampen brain function) can help people have the best brain function possible, but cannot make them entirely as they used to be.

So it is very important for both of you to invest some time and effort into cultivating your ability to cope with a new and changing “normal” in your life. If you are anxious and worried about him, you need to consider things like support groups, meditation or mindfulness-based stress reduction, enough exercise and sleep for yourself, and also education to help you learn to better manage your husband’s changing abilities.

I suppose that what I’m really saying is that you need to balance the pursuit of diagnosis and “medical” solutions with the accepting that a new and in many ways challenging reality is probably emerging. I see a lot of families neglect to take care of themselves and learn to better manage cognitive changes, because they are so caught up in the medical details. Good luck and take care.

Susan Stewart says

My husband has developed mild cognitive problems primarily visuospatial during the last year. He is seeing an psychiatrist who has not made a definite dx at present. His hx is of CVD and he had Triple Bypass surgery in 1984. He maintains a healthy diet, has excellent blood pressure, healthy weight and takes Aggrenox , crestor and Carvedilol. He had what was possibly a TIA last year with no residual. His MRI showed mild white matter T2 hyperintensities consistent with Chronic Small vessel ischemic changes expected for age. He also had a Carotid bilateral which showed a moderate amount of plaque. The MRI was repeated and showed minimum periventricular and brainstem chronic small vessel ischemic disease. Should he see a neurologist? Is it possible that the carotid artery problem could have caused the CSVD? Should we continue with testing for dementia or should we turn our attention to testing for the cause of the CSVD? What medications are effective for vascular dementia when a patient has depression and anxiety? my husband is 84 years Thanks for any help you can provide.

.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

If he is 84 and has a history of coronary artery disease, then I think an extensive workup for causes of cerebral small vessel disease is unlikely to be fruitful. Presumably he is getting good medical management to reduce his risk of future cardiovascular events; you say his cholesterol and BP are under good control, and he is taking an anti-platelet agent. There are other aspects he could consider, but honestly the older people are, the less effect those approaches seem to have on preserving cognition.

I have just recently written an article on cardiovascular risk factors: How to Address Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Better Brain Health: 12 Risks to Know & 5 Things to Do

For now, it’s likely to be more useful to focus on an evaluation of his cognitive impairment and to especially look for medical problems that might be causing or worsening his cognition (including medication side-effects). I explain such an evaluation here:

How We Diagnose Dementia: The Practical Basics to Know.

I list things that help optimize brain function (whether or not one has a dementia diagnosis) here: How to Promote Brain Health.

You should know that as people get into their 80s and beyond, it becomes extremely common for them to have multiple underlying causes of cognitive impairment. (This has been shown in autopsy studies.) But regardless of the underlying cause, the mainstay of optimizing people is to minimize the things that make them worse, and otherwise help them with whatever is hardest or most challenging for them. Good luck!

Steve says

Today my father took a brain MRI and received a referral like the one below.

The specialist’s appointment is next week, so I would like to ask for a brief explanation if possible.

In 2016, I was told that the stroke was recovering with a small stroke.

Below is a look at MRI imaging today.

about 2.7×3.0x3.1cm sized well defined cystic lesion at posterior midline of posterior crainal portion showing low SI on T1WI, bright high SI on T2WI.

Several small high SI lesions at both periventricular white matter on T2WI, FLAIR images.

No evidence of focal hemorrhagic foci or mass lesion in brain parenchyma.

No demonstrable widening of cisternal and ventricular system.

No demonstrable mass effect.

Otherwise unremarkable.

Conc) 1. Arachnoid cyst, posterior cranial fossa.

2. Chronic ischemic change, both periventricular white matter

rec) Clinical correction.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

The “chronic ischemic change” refers to what I describe in this article, meaning some form of cerebral small vessel disease. You may want to ask your health providers if it appears to be mild, moderate, or severe in extent.

You will need to ask the specialist whether the arachnoid cyst is concerning, or likely to be related to any symptoms you’ve observed. A study published in 2013 found that such cysts often tend to remain stable in size, with no new or worsening of symptoms.

Prevalence and natural history of arachnoid cysts in adults

You may also want to ask how the findings compare with whatever head imaging he had in 2016, when he was diagnosed with the small stroke.

You should know that “abnormal” findings are very common in the brains of older adults, so really hard part is figuring out whether they are related to concerning symptoms, and especially determining what to do, to improve or manage the symptoms. If they propose a procedure or intervention, always ask how likely it is to make a difference to your father’s health and abilities. Good luck!

Ken Roestenburg says

I have severe stenosis of the neck but No other risk factors of stroke. I recently had a stroke in the cerebellum that the have no identifying cause for. the most recent MRI showed the following results: MRI HEAD: No acute intracranial hemorrhage or abnormal extra

axial fluid collection.

No hydrocephalus. No mass, mass effect or midline shift. Basilar

cisterns are patent.

No acute ischemic infarct. Very small left inferior cerebellar

lesion corresponding to previous infarct, though smaller in

volume than the ischemic insult seen on original exam. Few

nonspecific punctate foci of white matter T2 prolongation, likely

reflecting sequela of chronic microvascular disease.

Orbits are unremarkable. No acute calvarial abnormality.

Extrarenal soft tissues and paranasal sinuses are unremarkable

FINDINGS: MRA NECK: There is markedly diminished caliber

throughout the course of the left vertebral artery just distal to

its origin. There is normal opacification of the posterior

circulation via the right vertebral artery. The bilateral

internal carotid arteries are normal in caliber and course.

Visualized Circle of Willis is unremarkable.

I am a 52 year old male, don’t drink, smoke, do not have high blood pressure, excersize daily, cholesterol was 90, all cardiology scans show no plaque build up nothing unusual. except the left vertabral artery. the neck MRI shows severe central, left and right formina stenosis at t1-c7, c7-c6, c6-c5, c4-c3. I have constant vertigo (3 to 4 times a day) could the stenosis be compressing the left artery and causing this??

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Sorry to hear of your health problems. Unfortunately, I’m not a neurologist and really don’t know if the foraminal stenoses you describe could cause the left artery vertebral compression and then the symptoms you have. I would recommend asking a neurologist, preferably one with experience managing these types of posterior circulation problems.

You might also want to ask the neurologist if your vertigo seems to be due to central causes or peripheral causes. I share some more information about vertigo and its evaluation in this comment above. Good luck and I hope you find some answers soon!

Davina says

Hello Dr.K

I am a 46 year old with mild small vessel ischemic disease, history of having silent strokes also. I have problems with balance, forgetting words how to say them, recently a small stutter at times or didn’t realize I did it tell I started using talk to txt repeating words or even sentences. I get dizzy drop things. Out of all the causes I dont have any except I am a smoker and family history of strokes and heart attacks. My question is how can or what do I need to do to slow this down. First is stop smoking and started that with chantx. Diet, natural herbs, vitamins? Thank you for your article also.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Stopping smoking is an excellent and very important start. Otherwise, I recommend you work in person with a good doctor, to get help determining which are your particular stroke risk factors and how they can be managed. For instance, are you quite sure that your blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, and inflammation levels are low? Especially if there is a family history of stroke or heart attacks, a careful evaluation of your health might reveal some risk factors that could be treated.

Taking specific vitamins or herbs is probably less helpful than overall eating a healthier Mediterranean-style diet, by which I mean one with a lot of vegetables, fruit, and fiber, minimal junk food or processed foods, and not too much red meat.

Last but not least, exercise exercise exercise.

You may want to start by focussing on staying off tobacco, exercising more, and eating better. That in of itself often improves a lot of the other cardiovascular risk factors. Good luck!

Sue L says

I am female, 67, with a history of controlled hypertension. As a result of a slip and fall last week, I had a head and brain CT scan which showed “mild asymmetry of the ventricles which are otherwise within normal limits for the patient’s age” and “mild cerebral atrophy,” and “Diffuse periventricular and deep white matter hypodensities are nonspecific, but are often associated with small vessel ischemic disease.” That led me to your article and I wish to thank you for your clear explanation of what is going on with my “aging” brain. I am prepared for a good discussion with my primary physician next month when I have my annual physical. Again, thank you for your clear explanations.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

I’m so glad to hear that you have found this article useful in preparing to talk with your physicians. I hope you’ll have a fruitful conversation about how you can address any cerebral small vessel risk factors you have.

When you see your doctor, you may want to review your blood pressure treatment plan. The latest high blood pressure guidelines were heavily influenced by the SPRINT blood pressure trial (which I explain in depth here). However, the sub-trial examining how intensive blood pressure treatment affects cognitive outcomes (SPRINT-MIND) has not yet been published.

As I explain in 6 Steps to Better High Blood Pressure Treatment for Older Adults, it’s essential to make sure your BP is being correctly measured (a single measurement taken in the office is not ideal), and it’s also essential to ask your doctors what they think your target BP should be, and why.

good luck!