This article is about the most common aging brain problem that you may have never heard of.

While leading a fall prevention workshop a few years ago, I mentioned that an older person’s walking and balance problems might well be related to the presence of “small vessel ischemic changes” in the brain, which are very common in aging adults. (This is also called “white matter disease.”)

This led to an immediate flurry of follow-up questions. What exactly are these changes, people wanted to know. Do they happen to every older adult? Is this the same as vascular dementia? And how they can best help their parents with cognitive decline?

Well, these types of brain lesions don’t happen to every older person, but they do happen to the vast majority of them. In fact, one study of older adults aged 60-90 found that 95% of them showed signs of these changes on brain MRI.

In other words, if your older parent ever gets an MRI of the head, he or she will probably show some signs of these changes.

So this is a condition that older adults and families should know about. Furthermore, these changes have been associated with problems of consequence to older adults, including:

- Cognitive decline,

- Problems with walking or balance,

- Strokes,

- Vascular dementia.

Now, perhaps the best technical term for what I’m referring to is “cerebral small vessel disease.” But many other synonyms are used by the medical community — especially in radiology reports. They include:

- White matter disease

- Small vessel ischemic disease

- Brain lesions

- Periventricular white matter changes

- Perivascular chronic ischemic white matter disease of aging

- Chronic microvascular changes, chronic microvascular ischemic changes

- Chronic microvascular ischemia

- White matter hyperintensities

- Age-related white matter changes

- Leukoaraiosis

In this post, I will explain what all older adults and their families should know about this extremely common condition related to the brain health of older adults.

In particular, I’ll address the following frequently asked questions:

- What is cerebral small vessel disease (SVD)?

- What are the symptoms of cerebral SVD?

- How is cerebral small vessel disease related to vascular dementia and cerebrovascular accidents?

- What causes cerebral SVD?

- How can cerebral SVD be treated or prevented?

- Should you request an MRI if you’re concerned about cerebral SVD?

I will also address what you can do, if you are concerned about cerebral SVD for yourself or an older loved one.

What is cerebral small vessel disease?

Cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is an umbrella term covering a variety of abnormalities related to small blood vessels in the brain. Because most brain tissue appears white on MRIs, these abnormalities were historically referred to as “white matter changes” or “white matter disease.”

Per this medical review article, specific examples of cerebral SVD include “lacunar infarcts” (which are a type of small stroke), “white matter hyperintensities” (which are a radiological finding), and “cerebral microbleeds” (which means bleeding in the brain from a very small blood vessel).

In many cases, cerebral SVD seems to be a consequence of atherosclerosis affecting the smaller blood vessels that nourish brain tissue. Just as one’s larger blood vessels in the heart or elsewhere can accumulate plaque, inflammation, and chronic damage over the years, so can the smaller blood vessels.

Such chronic damage can lead the small blood vessels in the brain to become blocked (which starves brain cells of oxygen, and which we technically call ischemia), or to leak (which causes bleeding, which we call hemorrhage and can damage nearby brain cells).

When little bits of brain get damaged in these ways, they can change appearance on radiological scans. So when an MRI report says “white matter disease,” this means the radiologist is seeing signs that probably indicate cerebral SVD.

(Note: In this podcast episode, a UCSF brain health expert explains that although cerebral small vessel disease is probably the most common cause of white matter changes in older adults, it’s not the only condition that can cause such changes. )

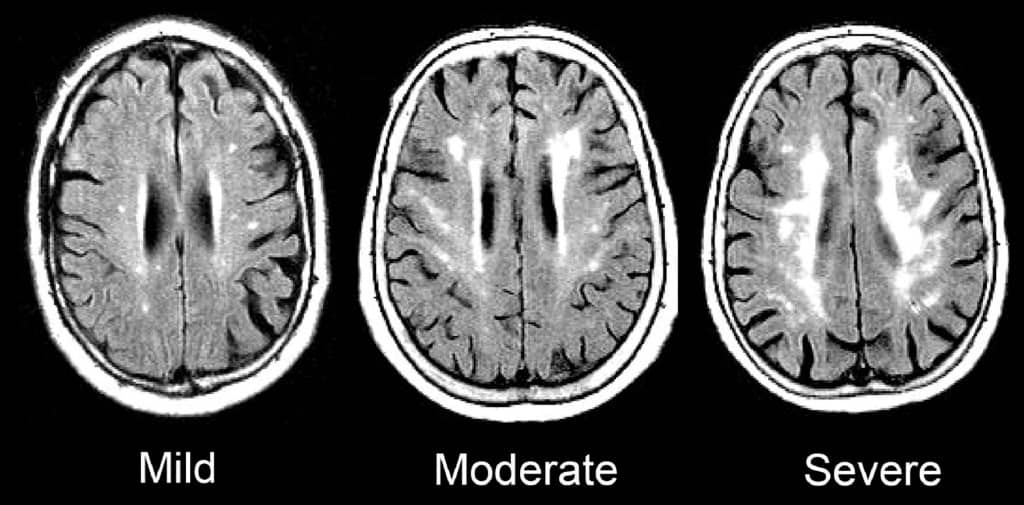

Such signs of SVD may be described as “mild”, “moderate,” or “severe/extensive,” depending on how widespread they are.

Here is an enlargement of a good image, from the BMJ article “Changes in white matter as determinant of global functional decline in older independent outpatients.”

What are the symptoms of cerebral small vessel disease?

The severity of symptoms tends to correspond to whether radiological imaging shows the white matter changes to be mild, moderate, or severe.

Many older adults with cerebral SVD will have no noticeable symptoms. This is sometimes called “silent” SVD.

But many problems have been associated with cerebral SVD, especially when it is moderate or severe. These include:

- Cognitive impairment. Several studies, such as this one, have found that cerebral SVD is correlated with worse scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam. When problems with thinking skills are associated with SVD, this can be called “vascular cognitive impairment.”

- Problems with walking and balance. White matter lesions have been repeatedly associated with gait disturbances and mobility difficulties. A 2013 study found that moderate or severe cerebral SVD was associated with a decline in gait and balance function.

- Strokes. A 2010 meta-analysis concluded that white matter hyperintensities are associated with a more than two-fold increase in the risk of stroke.

- Depression. White matter changes have been associated with a higher risk of depression in older people, and may represent a contributor to depression that is particular to having first-time depression in later life.

- Vascular dementia. Signs of cerebral SVD are associated with both having vascular dementia, and eventually developing vascular dementia.

- Other dementias. Research suggests that cerebral SVD is also associated with an increased risk — or increased severity — of other forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Autopsy studies have confirmed that many older adults with dementia show signs of both Alzheimer’s pathology and cerebral small vessel disease.

- Transition to disability or death. In a 2009 study of 639 non-disabled older persons (mean age 74), over a three-year follow-up period, 29.5% of participants with severe white matter changes and 15.1% of participants with moderate white matter changes developed disabilities or died. In comparison, only 10.5% of participants with mild white matter changes transitioned to disability or death over three years. The researchers concluded that severity of cerebral SVD is an important risk factor for overall decline in older adults.

So what does this all mean, in terms of symptoms and cerebral SVD? Here’s how I would boil it down:

1.Overall, older adults with any of the problems listed above have a high probability of having cerebral SVD.

2. But, many older adults with cerebral SVD on MRI are asymptomatic, and do not notice any difficulties. This is especially true of aging adults with mild cerebral SVD.

3. Older adults with cerebral SVD are at increased risk of developing the problems above, often within a few years time. This is especially true of people with moderate or severe cerebral SVD.

How is cerebral small vessel disease related to vascular dementia and cerebrovascular accidents?

The term “vascular dementia” means having dementia that is mostly due to having had problems with the blood vessels in the brain.

(For more on the definition of dementia and vascular dementia, see here: Beyond Alzheimer’s: Common Types of Dementia in Aging.)

The brain has some large blood vessels; when a person develops a clot or bleed related to a large blood vessel, this causes a major stroke, also known as a cerebrovascular accident.

It is possible to get dementia after a major stroke. However, in older adults, it’s probably more common to develop vascular dementia due to injuries to the small vessels of the brain. But again, as I explained above: not everyone with signs of cerebral small vessel disease ends up developing cognitive impairment or dementia.

What causes cerebral small vessel disease?

This is a topic of intense research, and the experts in this area tend to really nerd out when discussing it. (Read the scholarly papers listed below to see what I mean.) One reason it’s difficult to give an exact answer is that cerebral SVD is a broad umbrella term that encompasses many different types of problems with the brain’s small blood vessels.

Still, certain risk factors for developing cerebral SVD have been identified. Many overlap with risk factors for stroke. They include:

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia (e.g. high cholesterol)

- Atrial fibrillation

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Age

- Inflammation

There is also evidence that Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral small vessel disease frequently co-exist in older adults, and might interact to accelerate cognitive decline.

How can cerebral small vessel disease be treated or prevented?

Experts are still trying to figure out the answers to this question, and research into the prevention of cerebral SVD is ongoing.

Since worsening of white matter disease is often associated with clinical problems, experts are also trying to determine how we might prevent, or delay, the progression of SVD in older adults.

Generally, experts recommend that clinicians consider treating any underlying risk factors. In most cases, this means detecting and treating any traditional risk factors for stroke.

(For more on identifying and addressing stroke risk factors, see How to Address Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Better Brain Health: 12 Risks to Know & 5 Things to Do.)

To date, studies of hypertension treatment to prevent the progression of white matter changes have shown mixed results. It appears that treating high blood pressure can slow the progression of brain changes in some people. But such treatment may be less effective in people who are older than 80, or who already have severe cerebral SVD.

In other words, your best bet for preventing or slowing down cerebral SVD may be to properly treat high blood pressure and other risk factors before you are 80, or otherwise have significant SVD.

Furthermore, experts don’t yet agree on how low to go, when it comes to optimal blood pressure for an older person with cerebral small vessel disease. (This article explains why this has been difficult to determine.)

For now, to prevent the occurrence or progression of cerebral small vessel disease, it’s reasonable to start by observing the hypertension guidelines considered reasonable for most older adults: treat to a target of systolic blood pressure less than 150mm/Hg.

Whether to treat high blood pressure — and other cardiovascular risk factors — more aggressively should depend on an older person’s particular health circumstances. I explain a step-by-step process you can use (with links to related research) here: 6 Steps to Better High Blood Pressure Treatment for Older Adults.

You can also learn more about the research on CSVD and the effect of treating blood pressure here: The relation between antihypertensive treatment and progression of cerebral small vessel disease.

Not necessarily. In my opinion, older adults should only get MRIs of the brain if the following two things are true:

- They are experiencing worrisome clinical symptoms, and

- The results of the MRI are needed to decide on how to treat the person.

For most older adults, an MRI showing signs of cerebral SVD will not, in of itself, change the management of medical problems.

If you have high blood pressure, you should consider treatment. If you are having difficulties with walking or balance, signs of cerebral SVD do not rule out the possibility of other common causes of walking problems, such as medication side-effects, foot pain, neuropathy, and so forth.

What if you’re concerned about memory or thinking problems? Well, you probably will find signs of cerebral SVD on an MRI, just because this is a common finding in all older adults, and it’s especially common in people who are experiencing cognitive changes.

However, the MRI cannot tell you whether the cognitive changes you are noticing are only due to cerebral SVD, versus due to developing Alzheimer’s disease, versus due one of the many other dementia mimics. You will still need to pursue a careful evaluation for cognitive impairment. And no matter what the MRI shows, you will likely need to consider optimizing cardiovascular risk factors.

So in most cases, a brain MRI just to check for cerebral SVD is probably not a good idea.

However, if an MRI is indicated for other reasons, you may find out that an older person has mild, moderate, or severe signs of cerebral SVD. In this case, especially if the cerebral SVD is moderate or severe, you’ll want to consider taking steps to reduce stroke risk, and also to monitor for cognitive changes and increased disability.

What to do if you’re worried about cerebral small vessel disease

If you are worried about cerebral SVD, for yourself or for an older relative, here a few things you can do:

- Talk to your doctor about your concerns. You may want to discuss your options for optimizing vascular risk factors, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, high blood sugar, smoking, and others. For more on identifying and addressing stroke risk factors, see How to Address Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Better Brain Health: 12 Risks to Know & 5 Things to Do.

- Remember that exercise, a healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean diet), good sleep, stress reduction, and many other non-pharmacological approaches can help manage vascular risk factors. Lifestyle approaches are safe and usually benefit your health in lots of ways. Medications to treat high blood pressure and cholesterol should be used judiciously.

- If an MRI of the brain is clinically indicated — or if one has recently been done — ask the doctor to help you understand how the findings may correspond to any worrisome symptoms you’ve noticed. But if you’ve been worried about cognitive impairment or falls, remember that such problems are usually multi-factorial (i.e. they have multiple causes). So it’s best to make sure the doctors have checked for all other common contributors to thinking problems and/or falls.

If you want to learn still more about cerebral small vessel disease, here are some scholarly articles on the subject:

- CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review (2019)

- Mechanisms underlying sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging

- Causes and consequences of cerebral small vessel disease. The RUN DMC study

- Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (2011)

- Early Cerebral Small Vessel Disease and Brain Volume, Cognition, and Gait

- Cardiovascular risk factors and small vessel disease of the brain: Blood pressure, white matter lesions, and functional decline in older persons

I also recommend listening to this very informative podcast interview, with Dr. Fanny Elahi of the UCSF Memory and Aging Center: 084 – Interview: Understanding White Matter Changes in the Aging Brain.

Note: We’ve hit 300+ comments on this article! So we’re closing comments for this article. Thank you for your interest!

Note: This article has generated a lot of questions from people under age 60. If that describes you, please read below:

- Please read the article on “Early Cerebral Small Vessel Disease,” the full article is available for free. This describes SVD found in people aged 40-75. In this study, 2-3% of participants in their 40s showed signs of cerebral SVD.

- You can check for more recent research on this topic by entering the above article at scholar.google.com, and then click the “Cited by” link to find newer articles that reference this article.

- I do not know much about cerebral SVD in younger adults; this is not the population that I personally treat nor read much about. (I’m already quite busy trying to keep up with research related to older adults.)

- As best I can tell, most of what we currently know about health outcomes related to cerebral SVD is based on the studies of older adults. It is not clear to me whether people with cerebral SVD at younger ages should expect similar outcomes. I will not be able to answer most questions related to cerebral SVD in people under age 60.

- If you are concerned about what caused your MRI findings, or what they might mean for the future, please don’t ask me to tell you, because I don’t have these kinds of answers and I cannot quickly find them online.

- You should start by talking to your usual doctors, and perhaps a neurologist.

- If you would like to learn more, consider finding someone specialized in white matter disease in younger adults (e.g. someone doing and publishing research on this topic). Such experts are usually based at an academic medical center. Good luck!

Steven Burns says

Hi. I just read your article on Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Our 84 year old father suffered a sudden cardiac death event in 2000, and recovered, but was somewhat lethargic after that. 14 years later he was taken to the hospital with weakness, confusion, and poor gait. The CT scan said in part, “There is severe cerebral atrophy. There are extensive patchy ares of decreased density throughout the periventricular white matter consistent with small vessel ischemic changes. There is a more focal area of low attenuation adjacent to the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle consistent with an area of old infarct or eschemia.” Is this the disease you’re talking about?

11 days before going to the hospital, some people had him sign away some property, and I think he was taken advantage of. If this is a form of dementia, perhaps I should have someone look into this?

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

“Extensive patchy areas of decreased density throughout the periventricular white matter consistent with small vessel ischemic changes”, that would be consistent with cerebral small vessel disease. Whether or not that causes cognitive impairment would be hard to say with just MRI findings.

If your father was 84 in the year 2000 when he had his cardiac event, and then went to the hospital 14 years later, that would make him 98 when he went to the hospital in 2014. He certainly could have had dementia at that point, just based on statistics related to his age. You would need information on how his mental function was, in the weeks or months preceding hospitalization, and if you are wondering whether the property transaction was legitimate, you would need to get information to determine whether he had enough mental capacity at the time of signing the document.

(More on capacity here: Incompetence & Losing Capacity: Answers to 7 FAQs)

If you are wondering whether to “look into this”, I would recommend discussing with a qualified attorney. Especially if this took place years ago, there may be issues related to any relevant statute of limitations. Good luck!

Steven says

Thank you for your response. He was 70 in 2000, and 84 in 2014 when his property was taken. He died last week at 88. He was definitely vulnerable to exploitation. We’ll look into it. Thanks again for your kind response.

Yash says

My father who is now 60 years of age had a brain MRI done last week. He received the report saying he has chronic periventricular white matter microvascular angiopathic changes. He had been experiencing with seeing double things. He does have high blood pressure, and overweight. What is your take on this?

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

well, it sounds like he has signs of some cerebral small vessel disease. Some of it could be related to his weight and blood pressure, both of which are known cardiovascular risk factors.

I would recommend talking to his health providers about the findings. You may want to ask if the findings are likely to explain his double vision and other symptoms. Probably also a good idea to ask them to clarify that they think IS the most likely cause of his symptoms. good luck!

Anna Brown says

Hi Leslie, Thanks for your helpful articles. My 80 year old mother had a recent brain CT scan after hitting her head on a table. There was no damage from the fall but the report states ‘periventricular and deep white matter low attenuation, in keeping with chronic small vessel disease. Your articles mention mild, moderate and severe svd but not chronic. Can you please explain what this means. In the last year we’ve noticed she has increasing difficulty with word recall and often doesn’t speak in full sentences. She has type II diabetes. I’m following up your suggestions with her doctor regarding B12 and electrolyte imbalances. I got a copy of her latest blood tests which showed Creatinine level of 92umol but I don’t know if there’s anything we can do about this. She has a reasonably good diet and drinks plenty of water. Thanks

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Chronic means the damage to blood vessels doesn’t appear to be new, it is mainly to distinguish the finding from something that might be a new or acute stroke. Just about all cerebral small vessel disease findings on MRI are chronic.

If she is having trouble with recall or other cognitive functions, then she needs further evaluation. I explain what this usually entails in this article:

Cognitive Impairment in Aging: 10 Common Causes & 10 Things the Doctor Should Check.

Good luck!

Gaylen says

I am a 63 year old woman who has recently experienced falls leading to an MRI which revealed a 6mm leason which could be a meningioma and signs of CSVD. The second MRI with contour indicated the lesson grew to 7cm in a couple of months. My Mother died at age 66 from early onset dementia. I am not wanting an answer, l appreciate the opportunity to get this all out.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

So sorry to hear of your falls and recent MRI findings. This must be such a stressful time. I would encourage you to consider a support group of other people facing similar health challenges, either online or in person. I have never heard anyone say they regret reaching out to find support, but I’ve heard plenty of people say they should’ve done it sooner. Good luck and take care.

Donella says

Hi Dr Kernisan

I wonder if you received my previous comment regarding my Mum who’s 82 and recently been told she has extensive small vessel disease following an MRI scan she had due to possible TIAs ?

We feel that she shows no signs of having this disease other than the results of the scan. She leads a very healthy lifestyle in terms of both diet and excercise. She has been a vegetarian for 45 years and is very fit and young for her age. She has never smoked or drank alcohol. She seems completely with it mentally and is very mobile.

She is taking medications to keep her cholesterol at good levels, also blood pressure. The only other condition she has is burning mouth syndrome for which she has been in chronic pain for some 30 years. Is she likely to deteriorate rapidly, get dementia, have a stroke/heart attack? She feels like she’s been given a death sentence, whereas prior to the scan she always thought she would make 100 easily!

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Hm, this is the only comment I see in the system associated with your email address; sorry if a previous comment disappeared into the online ether.

That is interesting that your mother is being told she has “extensive small vessel disease” despite a very healthy lifestyle. Her doctors are best positioned to counsel her on what to expect. That said, I would say that if she’s feeling quite physically and mentally fit, that’s very encouraging. The correlation between what is seen on imaging and the symptoms people experience is quite variable. I would not expect her to deteriorate rapidly, but over the next 10 years, it’s certainly possible that she could develop some memory/thinking difficulties, or other problems related to cerebral SVD.

Regarding her risk for a stroke or heart attack, you could try using the online CV risk calculator. Technically it is only valid for people up to age 79, but at 82, she is close, so you will still get a ballpark estimate.

ASCVD Risk Calculator (American College of Cardiology)

In general, just about everyone in their 80s has a fair chance of experiencing a heart attack or stroke over the next 10 years, because age is such a strong risk factor. I often tell my patients to hope for the best but plan for the possible. It is good to cultivate an attitude of acceptance. No one knows what the future holds, so all you can do is make a good effort to take care of yourself, plan for the possibility of a health crisis or decline in the future (do it for your family’s sake if not for yourself) and otherwise try to enjoy the present moment. Good luck!

Donella says

Thank you for your reply and advice. I have read your comment to my Mum and she is more hopeful. She has a second appointment at the end of this month. I may update then with their findings.

Wishing you all the best.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Hope in the face of uncertainty and eventual problems is essential. Take care and do keep us posted!

Traci says

I had a strange seizure/stroke attack 1 1/2 years ago. They ruled out stroke at the ER. But reading my MRI it mentions hyperintensity in the left frontal lobe that may be related to small vessel ischemic change. I have just been diagnosed with Complex Partial Seizures. Can this be related?

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

I know very little about seizures and don’t know how they relate to small vessel damage in the brain. I would recommend addressing your question to a neurologist, preferably one who specializes in seizures.

Troy Taylor says

Hello Dr. Kernisan, I’m 49 and my Dr just informed me I show early signs of small vessel disease. I have a history of high cholesterol and was at one time borderline diabetic but have that under control now. I am overweight but working to turn that around with diet and excercise. She already has me on a cholesterol medication and advised I start taking a daily baby aspirin. Just wander what your take on this is? Thank you

Btw I had an MRI done due to headaches, problems with concentration and memory..

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

My understanding is that research is still ongoing, regarding the role of aspirin in managing people with signs of cerebral small vessel disease. The state of the science was summarized in December 2016 here:

Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Silent Cerebrovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association

Generally, daily aspirin is recommended as “secondary prevention” (to prevent a subsequent event) for people who have had a heart attack, stroke, or other significant cardiovascular event. For people who have never had an event, aspirin can be considered for those who seem to be at particularly high risk.

The difficulty is that in medicine we are still unsure as to how to classify these small and often “silent” events that show up on brain MRIs.

You may want to ask your doctor to clarify how she is calculating your risk for cardiovascular disease in general. There are well known calculators that can be used online. Otherwise, my related article on addressing cardiovascular risk factors. Good luck!

Terri says

I am 63 and recently had a severe headache in the back of my head that lasted for about 10-20 seconds and was associated with orgasm. Never had it before. My doctor ordered and MRI/MRA w/wo contrast as he said that was the protocol for my symptoms.

Impression:

1) no acute intracranial pathology

2) mild volume loss and mild chronic small vessel ischemic disease.

My doctor said my MRI/MRA were normal. By your article it doesn’t appear that is correct.

I work full time, have never been overweight, have never had HTN, take no medicine except vitamins. No headaches, migraines etc. Excercise and do eat healthy 95% of the time.

Your thoughts? Is this really considered normal?

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Well, sometimes it is tricky to say what is “normal.” It is certainly common for people to develop signs of cerebral small vessel disease as they get older, and it’s also common for them to develop some volume loss of the brain. Whether to consider it “abnormal” depends on whether it’s more than expected for someone your age and whether it’s considered to be reflective of an “abnormal” process as opposed to more “normal” or “usual” age-related changes. My understanding is that researchers are still trying to sort this out.

A study published in 2017 did find that inflammation is associated with brain volume changes later in life:

Midlife systemic inflammatory markers are associated with late-life brain volume

There is some evidence that our typical modern lifestyle (sub-optimal diet, stressful lives, not enough sleep, etc) contributes significantly to chronic inflammation and that this results in more wear on the body and brain.

If you have questions about your MRI findings, you should discuss them with your doctor. You may also want to consider getting a second opinion from a doctor with experience in neuroradiology. Good luck!

B Jeanne Hansen says

I am 75. I first had difficulty starting in 1990 with fatigue, fibromyalgia, difficulty finding words and mild depression. MRI showed large amt. of white matter changes, and it was considered multiple infarcts and more typically MS. I saw a neurologist for awhile, and also had psychometric tests. They showed a decline over a few years of sequencing. I also received counseling. I had depression caused PTSD. I stopped taking Copaxone in 2008 because I got a SVD diagnosis from Mayo’s

Although Mayo called this SVD, I still wonder about MS. I think because of the recent decline I should be rechecked. I take cholesterol meds, 4 different antidepressants, (flexeril, tramadol, Nortriptyline and Ambien at night.) Occasionally I take an extra tramadol and or flexural in the daytime. I take up to 4 tablets of Naprosyn a day. I use 8 hour hot packs on my neck frequently and have had wrist, elbow and heel tendonitis on occasion with PT to reduce symptoms. I returned to playing water-volleyball this past week. I have been doing this since shortly after my MS diagnosis. It is hard to get there on time. I would like arrive earlier to do water aerobics but seldom do. I am avoiding stress as much as possible during this busy time.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Your medical history sounds exceptionally complicated. If you have noticed recent declines, then getting re-evaluated or getting a second opinion certainly sounds reasonable.

If you have noticed any difficulties or declines in memory or thinking abilities, then you may want to discuss your medications in more detail with your doctors. Several of the ones you are taking interfere with brain function, so it’s important to be sure that the benefits outweigh the risks, and that you are taking the minimum doses needed to manage your symptoms and conditions. Good luck!

sharon says

My husband, now 73 was diagnosed with vascular dementia (early stages) 2 years ago. Since then he had been quite stable. He has recently been in hospital following a chest infection. On admission his gait & balance were poor, he was confused & generally very unwell. An MRI showed small vessel disease. He is home now, has to use a walking frame & his balance is poor. Mentally, he is pretty much the same as before hospitalisation. He has been told that he mustn’t drive again. What sort of prognosis, in your opinion, does he have & as his sole career, what should I expect? Thank you.

Leslie Kernisan, MD MPH says

Not sure what you mean by prognosis, do you mean his life-expectancy or more generally what to expect in the future?

My experience has been that the progression of vascular dementia is quite variable; some people seem to stay with the same level of difficulties for a while, whereas others decline more steadily, or with a “step” downwards (which may reflect something like a small stroke or can be provoked by a serious illness) intermittently.

I would recommend you ask his usual doctors for more information as to his prognosis and what to expect.

In general, people with dementia tend to get worse over time. It’s hard to know exactly when or how that will happen, but in planning for the future, it’s generally a good idea to assume the person may well need more hands-on care over time, and to think about how you might manage if that comes to pass. A local or online dementia support group can be very helpful in thinking these kinds of things through. Good luck!